I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

| I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud | |

|---|---|

| by William Wordsworth | |

A hand-written manuscript of the poem (1804). British Library Add. MS 47864[1] |

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

– William Wordsworth (1802)

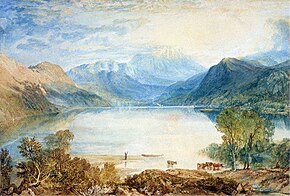

"I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" (also sometimes called "Daffodils"[2]) is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth.[3] It is one of his most popular, and was inspired by an encounter on 15 April 1802 during a walk with his younger sister Dorothy, when they saw a "long belt" of daffodils on the shore of Ullswater in the English Lake District.[4] Written in 1804,[5] this 24 line lyric was first published in 1807 in Poems, in Two Volumes, and revised in 1815.[6]

In a poll conducted in 1995 by the BBC Radio 4 Bookworm programme to determine the nation's favourite poems, I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud came fifth.[7] Often anthologised, it is now seen as a classic of English Romantic poetry, although Poems, in Two Volumes was poorly reviewed by Wordsworth's contemporaries.

Background

[edit]The inspiration for the poem came from a walk Wordsworth took with his sister Dorothy around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District.[8][4] He would draw on this to compose "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" in 1804, inspired by Dorothy's journal entry describing the walk near a lake at Grasmere in England:[8]

Gobarrow Park is on the north side of Ullswater, so Wordsworth's daffodils would have been on the nearer shore – near the cows perhaps?

When we were in the woods beyond Gowbarrow park we saw a few daffodils close to the water side, we fancied that the lake had floated the seed ashore and that the little colony had so sprung up – But as we went along there were more and yet more and at last under the boughs of the trees, we saw that there was a long belt of them along the shore, about the breadth of a country turnpike road. I never saw daffodils so beautiful they grew among the mossy stones about and about them, some rested their heads upon these stones as on a pillow for weariness and the rest tossed and reeled and danced and seemed as if they verily laughed with the wind that blew upon them over the Lake, they looked so gay ever glancing ever changing. This wind blew directly over the lake to them. There was here and there a little knot and a few stragglers a few yards higher up but they were so few as not to disturb the simplicity and unity and life of that one busy highway – We rested again and again. The Bays were stormy and we heard the waves at different distances and in the middle of the water like the Sea.[9]

— Dorothy Wordsworth, The Grasmere Journal Thursday, 15 April 1802

At the time he wrote the poem, Wordsworth was living with his wife, Mary Hutchinson, and sister Dorothy at Town End,[Note 1] in Grasmere in the Lake District.[10] Mary contributed what Wordsworth later said were the two best lines in the poem, recalling the "tranquil restoration" of Tintern Abbey,[Note 2]

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude

Wordsworth was aware of the appropriateness of the idea of daffodils which "flash upon that inward eye" because in his 1815 version he added a note commenting on the "flash" as an "ocular spectrum". Coleridge in Biographia Literaria of 1817, while acknowledging the concept of "visual spectrum" as being "well known", described Wordsworth's (and Mary's) lines, among others, as "mental bombast". Fred Blick[11] has shown that the idea of flashing flowers was derived from the "Elizabeth Linnaeus phenomenon", so called because of the discovery of flashing flowers by Elizabeth Linnaeus in 1762. Wordsworth described it as "rather an elementary feeling and simple impression (approaching to the nature of an ocular spectrum) upon the imaginative faculty, rather than an exertion of it..."[12] The phenomenon was reported upon in 1789 and 1794 by Erasmus Darwin, whose work Wordsworth certainly read.

The entire household thus contributed to the poem.[5] Nevertheless, Wordsworth's biographer Mary Moorman notes that Dorothy was excluded from the poem, even though she had seen the daffodils together with Wordsworth. The poem itself was placed in a section of Poems in Two Volumes entitled "Moods of my Mind" in which he grouped together his most deeply felt lyrics. Others included "To a Butterfly", a childhood recollection of chasing butterflies with Dorothy, and "The Sparrow's Nest", in which he says of Dorothy "She gave me eyes, she gave me ears".[13]

The earlier Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by both Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, had been first published in 1798 and had started the romantic movement in England. It had brought Wordsworth and the other Lake poets into the poetic limelight. Wordsworth had published nothing new since the 1800 edition of Lyrical Ballads, and a new publication was eagerly awaited.[14] Wordsworth had gained some financial security by the 1805 publication of the fourth edition of Lyrical Ballads; it was the first from which he enjoyed the profits of copyright ownership. He decided to turn away from the long poem he was working on (The Recluse) and devote more attention to publishing Poems in Two Volumes, in which "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" first appeared.[15]

Revision

[edit]

Wordsworth revised the poem in 1815. He replaced "dancing" with "golden"; "along" with "beside"; and "ten thousand" with "fluttering and". He then added a stanza between the first and second, and changed "laughing" to "jocund". The last stanza was left untouched.[16]

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

and twinkle on the Milky Way,

They stretched in never-ending line

along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

in such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

what wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

Pamela Woof wrote that "The permanence of stars as compared with flowers emphasises the permanence of memory for the poet."[17] Andrew Motion, in a piece about the enduring appeal of the poem, wrote that "the final verse ... replicates in the minds of its readers the very experience it describes".[12]

Reception

[edit]Contemporary

[edit]

Poems, in Two Volumes was poorly reviewed by Wordsworth's contemporaries, including Lord Byron, whom Wordsworth came to despise.[18] Byron said of the volume, in one of its first reviews, "Mr. [Wordsworth] ceases to please, ... clothing [his ideas] in language not simple, but puerile".[19] Wordsworth himself wrote ahead to soften the thoughts of The Critical Review, hoping his friend Francis Wrangham would push for a softer approach. He succeeded in preventing a known enemy from writing the review, but it did not help; as Wordsworth himself said, it was a case of, "Out of the frying pan, into the fire". Of any positives within Poems, in Two Volumes, the perceived masculinity in "The Happy Warrior", written on the death of Nelson and unlikely to be the subject of attack, was one such. Poems like "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" could not have been further from it. Wordsworth took the reviews stoically.[14]

Even Wordsworth's close friend Coleridge said (referring especially to the "child-philosopher" stanzas VII and VIII of "Intimations of Immortality") that the poems contained "mental bombast".[20] Two years later, many were more positive about the collection. Samuel Rogers said that he had "dwelt particularly on the beautiful idea of the 'Dancing Daffodils'", and this was echoed by Henry Crabb Robinson. Critics were rebutted by public opinion, and the work gained in popularity and recognition, as did Wordsworth.[12]

Poems, in Two Volumes was savagely reviewed by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review (without singling out "I wandered lonely as a Cloud"), but the Review was well known for its dislike of the Lake Poets. As Sir Walter Scott put it at the time of the poem's publication, "Wordsworth is harshly treated in the Edinburgh Review, but Jeffrey gives ... as much praise as he usually does", and indeed Jeffrey praised the sonnets.[21]

Upon the author's death in 1850, The Westminster Review called "I wandered lonely as a Cloud" "very exquisite".[22]

Settings to music

[edit]The poem has been set to music, for example by Eric Thiman in the 20th century. In 2007, Cumbria Tourism released a rap version of the poem, featuring MC Nuts, a Lake District red squirrel, in an attempt to capture the "YouTube generation" and attract tourists to the Lake District. Published on the two-hundredth anniversary of the original, it attracted wide media attention.[23] It was welcomed by the Wordsworth Trust,[24] but attracted the disapproval of some commentators.[25]

In 2019 Cumbria Rural Choirs with help from the Leche Trust commissioned a setting by Tamsin Jones, which was to have been performed in March 2020 at Carlisle Cathedral with British Sinfonietta,[26] but because of COVID restrictions in the UK the premiere was delayed until 2022.[27]

Modern usage

[edit]The poem is presented and taught in many schools in the English-speaking world.

UK

[edit]These include the English Literature GCSE course in some examination boards in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. In 2004, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the writing of the poem, it was read aloud by 150,000 British schoolchildren, aimed both at improving recognition of poetry and supporting Marie Curie Cancer Care (which uses the daffodil as a symbol, for example in the Great Daffodil Appeal).[28]

Abroad

[edit]It is used in the current Higher School Certificate syllabus topic, Inner Journeys, New South Wales, Australia. It is also frequently used as a part of the Junior Certificate English Course in Ireland as part of the Poetry Section. The poem is also included in the syllabus for the Grade IX (SSC-1) FBISE examinations, Pakistan and the Grade X ICSE (Indian Certificate of Secondary Education) examinations, India.

V. S. Naipaul, who grew up in Trinidad when it was a British colony, mentions a "campaign against Wordsworth" in the island, which he did not agree with. It was argued that the poem should not be in the syllabus because "daffodils are not flowers Trinidad schoolchildren know" .[29] Jean Rhys, another writer who was born in the British West Indies, objected to daffodils through one of her characters. It has been suggested that colonisation of the Caribbean resulted in a "daffodil gap".[30] This refers to the perceived difference between the lived experience and imported English literature.

In popular culture

[edit]- In the 2013 musical Big Fish, composed by Andrew Lippa, some lines from the poem are used in the song "Daffodils", which concludes the first act. Lippa mentioned this in a video created by Broadway.com in the same year.[31]

- In Gucci's Spring/Summer 2019 Collection, multiple ready-to-wear pieces featured embroidery of the last lines of the poem.[32]

- The poem is used in a segment of the Emergency! episode "Body Language," which aired on December 7, 1973. In the segment, a young lady was reciting part of the poem ad naseam after she and her boyfriend had consumed daffodil bulbs.

Parodies

[edit]Because it is one of the best-known poems in the English language, it has frequently been the subject of parody and satire.[33]

The English prog rock band Genesis parodies the poem in the opening lyrics to the song "The Colony of Slippermen", from their 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

It was the subject of a 1985 Heineken beer TV advertisement, which depicts a poet having difficulties with his opening lines, only able to come up with "I walked about a bit on my own" or "I strolled around without anyone else" until downing a Heineken and reaching the immortal "I wandered lonely as a cloud" (because "Heineken refreshes the poets other beers can't reach").[34][35] The assertion that Wordsworth originally hit on "I wandered lonely as a cow" until Dorothy told him "William, you can't put that" occasionally finds its way into print.[36]

Tourism and exhibitions in Cumbria

[edit]Two important tourist attractions in Cumbria are Wordsworth's homes Dove Cottage with its adjacent visitors centre and Rydal Mount. They have hosted exhibitions related to the poem. For example, in 2022 the British Library's unique manuscript of the poem was lent to the Wordsworth Trust as part of a "treasures on tour" programme. It went on display in Grasmere alongside the Trust's own copy of Dorothy Wordsworth's Grasmere journal.[37]

There are still daffodils to be seen in the county. The daffodils Wordsworth described would have been wild daffodils.[38] The National Gardens Scheme runs a Daffodil Day every year, allowing visitors to view daffodils in Cumbrian gardens including Dora's Field, which was planted by Wordsworth.[39] In 2013, the event was held in March, when unusually cold weather meant that relatively few of the plants were in flower.[40] April, the month that Wordsworth saw the daffodils at Ullswater, is usually a good time to view them, although the Lake District climate has changed since the poem was written.[41]

200th anniversary

[edit]In 2015, events marking the 200th anniversary of the publication of the revised version were celebrated at Rydal Mount.[42]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Their cottage is known as Dove Cottage today, but in fact it had no name in their time and their address was simply "Town End, Grasmere", Town End being the name of the hamlet in Grasmere they lived in. See Moorman (1957). pp. 459–460.

- ^ In the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads Wordsworth famously defined poetry as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity." Mary Moorman (1957 pp. 148–149) remarks that in this manner spring poems such as "Tintern Abbey" and "I wandered lonely as a Cloud", as well as all the best of The Prelude.

References

[edit]- ^ Wordsworth, William. "I wandered lonely as a cloud". British Library Images Online. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "William Wordsworth (1770–1850): I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud". Representative Poetry Online. 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ "Historic figures: William Wordsworth (1770–1850)". BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ a b Radford, Tim (15 April 2011). "Weatherwatch: Dorothy Wordsworth on daffodils". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ a b Moorman (1965) p. 27

- ^ Magill, Frank Northen; Wilson, John; Jason, Philip K. (1992). Masterplots II. (Goa-Lov, Vol. 3). Salem Press. p. 1040. ISBN 978-0-89356-587-9.

- ^ Gryff Rhys Jones, ed. (1996). The Nation's Favourite Poems. BBC Books. p. 17. ISBN 0563387823.

- ^ a b "Daffodils at Glencoyne Bay". Visit Cumbria. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Wordsworth ed. Woof (2002) p. 85

- ^ The Wordsworth Trust. "Dove Cottage". The Wordsworth Museum & Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Blick, Fred (22 February 2017). "'Flashes upon the inward eye' : Wordsworth, Coleridge and 'Flashing Flowers'".

- ^ a b c Motion, Andrew (6 March 2004). "The host with the most". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ Moorman (1965) pp. 96–97

- ^ a b Davies, Hunter (2009). William Wordsworth. Frances Lincoln Ltd. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-7112-3045-3. Retrieved 30 December 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Johnston, Kenneth R. (1998). The Hidden Wordsworth. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 822–823. ISBN 0-393-04623-0.

- ^ "I wandered lonely as a Cloud by William Wordsworth". The Wordsworth Museum & Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Pamela Woof (November 2009). "The Wordsworths and the Cult of Nature:The daffodils". British History in-depth. BBC. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ "William Wordsworth". Britain Express. 2000. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ Byron, Baron George (1837). The works of Lord Byron complete in one volume. H.L. Broenner. p. 686.

- ^ Hill, John Spencer. "The Structure of Biographia Literaria". John Spencer Hill (self-published). Archived from the original on 5 July 2012.

- ^ Woof, Robert; et al. (2001). William Wordsworth: the critical heritage. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-415-03441-8.

- ^ "The Prelude..." The Westminster Review. 53 (October). New York: Leonard Scott and Co.: 138 1850.

- ^ "Poem set to rap to lure visitors". BBC. April 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Martin Wainwright (April 2007). "Respect for Wordsworth 200 years on with daffodil rap". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Ben Marshall (April 2007). "Romantic poetry will never rock the house". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ "Choir to commemorate William Wordsworth with a special concert". 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Wordsworth 250 | A Year-Long Celebration of William Wordsworth's Birth".

- ^ "Mass recital celebrates daffodils". BBC. March 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Naipaul, V. S. (1963) [first published 1962]. The Middle Passage. London: Readers Union. p. 65.

- ^ Sue Thomas, "Genealogies of Story in Jean Rhys’s 'The Day They Burned the Books'", The Review of English Studies, Volume 72, Issue 305, June 2021, Pages 565–576, https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgaa084

- ^ Broadwaycom (25 September 2013), Composer Andrew Lippa Sits Down at the Piano to Share the Larger-Than-Life Tales of "Big Fish", retrieved 29 November 2016

- ^ "black cotton Embroidered sweatshirt | GUCCI® US". 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Rilkoff, Matt (27 December 2011). "Greenie of the week: William Wordsworth". Taranaki Daily News. p. 14.

- ^ "Flowery language". Scottish Poetry Library. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ AdstudiesFocusBeers (25 March 2013), Heineken Lager – Wordsworth – I walked about a bit on my own..., retrieved 2 October 2018

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (20 March 2012). "The ruthless side of William Wordsworth". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ "William Wordsworth Daffodils". February 2022.

- ^ McCarthy, Michael (March 2015). "I wandered lonely through a secret daffodil wood". Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "From Cartmel to Carlisle. Wordsworth's Daffodil Legacy". National Gardens Scheme. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Opportunity to view host of golden daffodils". Westmorland Gazette. March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (March 2012). "The ruthless side of William Wordsworth". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Exhibition tribute to Wordsworth's Daffodils". Cumbria Crack: Breaking News Penrith, Cumbria, Carlisle, Lake District. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Davies, Hunter. William Wordsworth, Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1980

- Gill, Stephen. William Wordsworth: A Life, Oxford University Press 1989

- Moorman, Mary. William Wordsworth, A Biography: The Early Years, 1770–1803 v. 1, Oxford University Press 1957

- Moorman, Mary. William Wordsworth: A Biography: The Later Years, 1803–50 v. 2, Oxford University Press 1965

- Wordsworth, Dorothy (ed. Pamela Woof). The Grasmere and Alfoxden Journals. Oxford University Press 2002

External links

[edit]- Daffodils, The Wordsworth Trust

- Information about William Wordsworth

- Facsimile of Dorothy's "daffodils" entry in her journal

- Google Books archive of Poems in Two Volumes Volume II

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud public domain audiobook at LibriVox

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Preface to Lyrical Ballads

- Google Books archive of Francis Jeffrey's review of Poems in Two Volumes

- "Daffodils" set to music[permanent dead link] From the 1990 concept album "Tyger and Other Tales"

- I wandered lonely as a Cloud (Daffodils), Theme of Man and the Natural World